Timberlands Biodiversity and Wildlife

Committed to Stewardship

Sustainably managed private working forests are healthy and resilient and provide forest habitat that supports a significant amount of the forest species. Our forest stewardship commitments include the responsibility to conserve wildlife species and their habitats.

CONSERVING BIODIVERSITY

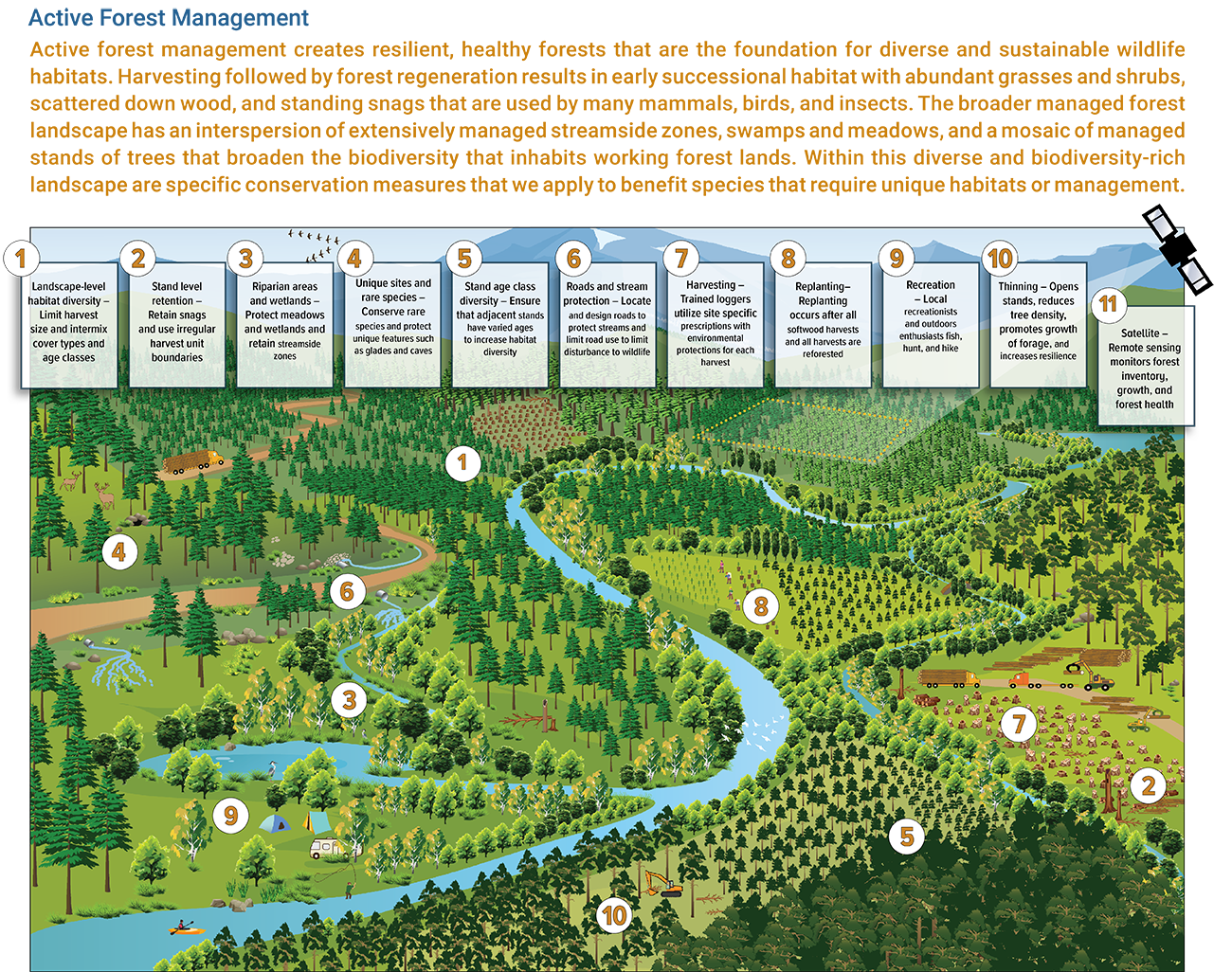

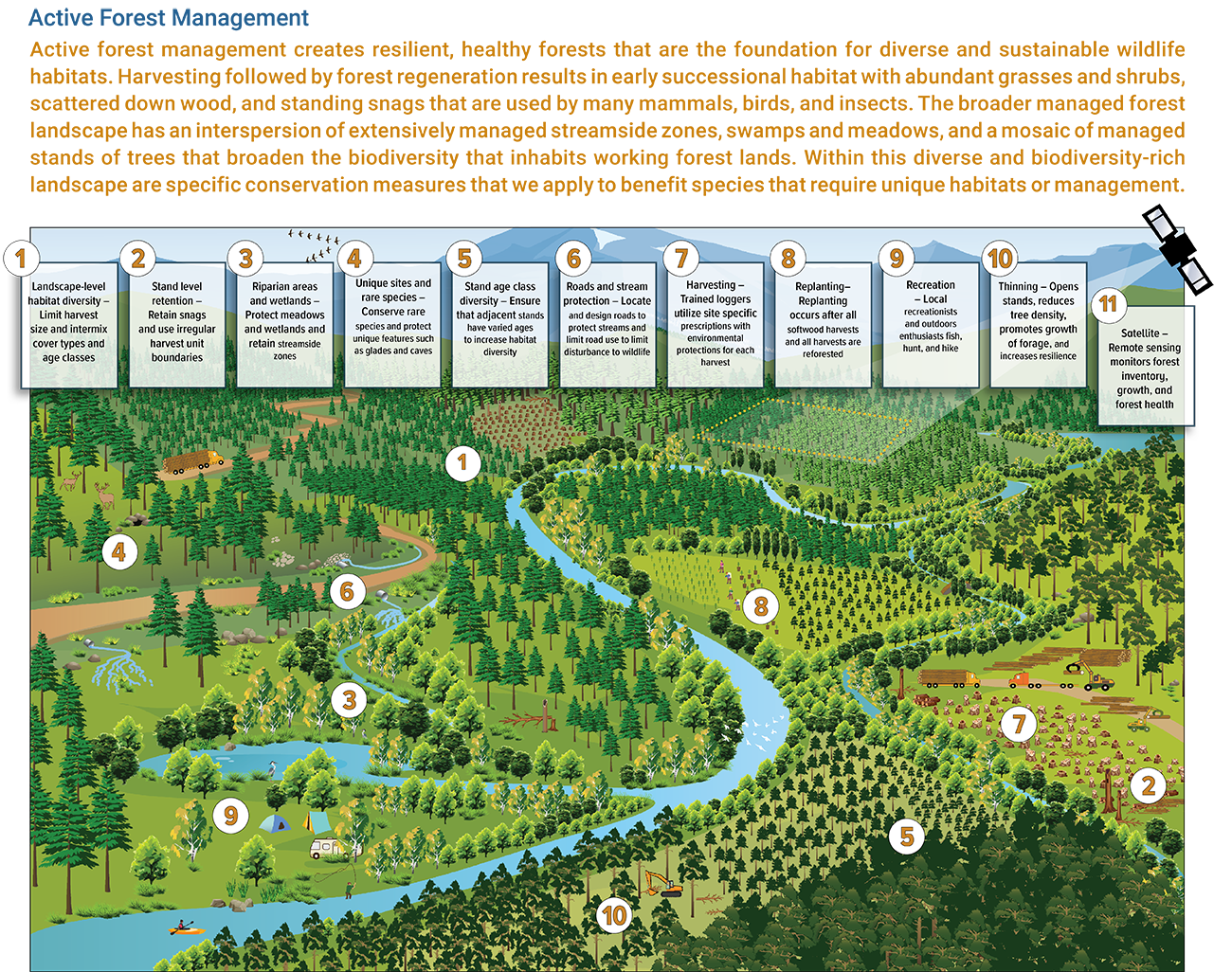

Forests are diverse ecological systems with habitats for plants, animals, and organisms. Active forest management is a valuable tool for creating and maintaining a wide range of biodiversity benefits, enabling forests to stay healthy and productive. Across a landscape, a mosaic of forest ages from recently harvested to mature forests can be maintained – these forests in turn support long-term viability of wildlife species, plants, and biodiversity. At a broader scale, managed forests can provide habitat connectivity and help maintain and enlarge intact forested areas.

Markets for forest products provide an incentive to conserve forests as forests compared to alternative land uses that are not as beneficial to water quality, wildlife habitat, carbon sequestration and recreation. Healthy and vigorously managed forests are also less susceptible to catastrophic loss from insects, disease, and wildfire.

Our commitment to conserving biodiversity on our forest lands is based on this recognition that well-managed working forest lands provide a broad range of habitats for aquatic, avian, and terrestrial biodiversity. Four main components comprise our approach to assessing dependency- and impact- related biodiversity risks to maintaining and enhancing biodiversity: (1) landscape-level management; (2) stand-level diversity; (3) protection of ecologically unique sites or species; and (4) research.

We provide habitat diversity at the landscape level by utilizing stand size and age class adjacency restrictions for final harvest, identifying streamside management zones, maintaining a diversity of cover types, and replanting native species. The managed landscape provides a mixture of forest structure, age classes, and cover types, intermingled with less intensively managed riparian areas and embedded conservation of unique sites. Diverse working forest landscapes provide abundant habitat for large ungulates such as deer, elk and moose and a wide diversity of birds such as red-bellied woodpeckers, prairie warblers and wild turkeys.

We achieve stand-level diversity that enhances habitat for a variety of wildlife species through site-specific forest management including planning, implementation, and evaluation. Stand level diversity techniques include retaining unharvested areas, retention of den trees or snags, retention of slash piles, utilizing irregularly shaped openings, and protection of non-forested areas such as glades, meadows, and non-forested wetlands.

We protect ecologically unique sites or species by identifying sites with species or communities that are unique, rare, or listed as federally threatened or endangered through exchange of data with state natural heritage programs, NatureServe, state wildlife agencies, and by internal discovery. Site locations are then mapped and included in our Land Resource Manager system. Screening is done systematically at a site level and looks at adjacent lands in higher risk areas to help mitigate risk. Foresters use this proprietary, real-time information when preparing detailed harvest plans to ensure these unique features are incorporated into our management plans.

PotlatchDeltic has a long and continuing commitment to investing in and utilizing research to improve biodiversity conservation and environmental protection. We actively participate in and fund research with NCASI, universities, and fish and wildlife organizations to understand habitat and biodiversity response to forest management and then integrate research findings into our management. In addition, we actively advocate for laws and regulations that protect fish and wildlife and promote practical approaches that recognize the benefits of working forest lands.

IDAHO BIODIVERSITY MANAGEMENT

Our wildlife and biodiversity management in Idaho focuses on a wide range of animals, fish, and plants. In northern Idaho, elk, deer, and moose are vitally important to rural communities’ culture, traditions and economy and serve societal needs as game animals or subsistence foods. These large ungulates can also affect native vegetation and agricultural crops because of their large body size, diet choices, and widespread distributions. PotlatchDeltic recognizes the importance of these species and maintaining healthy herds in balance with native vegetation. As a result, we have made substantial commitments to research, conservation, and public recreation through partnerships with Idaho Department of Fish and Game (IDFG) and others. Our partnership with IDFG has continued to grow and includes efforts to balance recreational use with resource protection by ensuring that vehicle access is planned to limit disturbance to wildlife and allows full utilization of habitat by deer, elk, and moose.

The Westslope cutthroat trout is native to our northern Idaho forest lands and occupies many of the headwater streams within our actively managed working forests. They feed primarily on aquatic insect life and zooplankton. Cutthroat spawn in tributary streams in the springtime when water temperature is about 10 degrees C and flows are high with spring run-off, burying their eggs in a nest called a redd. The eggs hatch in a few weeks to a couple of months and most of the cutthroat remain as resident fish and spend their entire life in these tributary streams within our forests. Our Mica Creek Research project has demonstrated that the contemporary BMPs, which are the foundation of the Idaho Forest Practices Act, fully provide cutthroat conservation. The Mica study has consistently shown that cutthroat increase in number and extent when forest harvest occurs within the cold and nutrient-poor headwater stream watersheds.

The PotlatchDeltic northern Idaho timberlands are home to a broader range of biodiversity that, while not as notable as elk and cutthroat, are an important part of our conservation efforts. These range from the many types of fungus that emerge in our conifer stands such as morel mushrooms, which tend to show up in newly planted stands in the spring, to the angel wing mushroom that grows on the sides of conifer trees and are widely sought by animals for their forage value. There are also the Clearwater Phlox and the northern goshawk. The phlox and goshawk are both species that are identified in our GIS map layer of biodiversity and that we have conservation protocols for within our EMS.

U.S. SOUTH BIODIVERSITY MANAGEMENT

Our southern timberlands have long growing seasons and plentiful rainfall that make a very productive system that supports a tremendous diversity of animals and plants. And in many cases, lots of them! On a spring day in our southern working forest the sounds of native birds singing, frogs calling and croaking, and the buzz of native bees can make for a noisy workplace for our foresters. Just the chirps of spring peepers, small chorus frogs, can reach the level where it is hard to hear much else.

Southern working forests have been documented to have more than 80 breeding bird species and many more species that migrate through twice a year. Forest lands at different stages of management and ages can be a boon to southern birds. A few examples of bird-benefiting forest management practices include riparian buffers that protect not only water quality but also Swallow-tailed Kites and Hooded Warblers and provide their nesting habitat. Mixed forest stands are home to Pileated Woodpeckers, Red-shouldered Hawks, and Barred Owls. Regenerating pine forests are important for the Prairie Warbler and Northern Bobwhite. Prairie Warblers are known to prefer recently thinned stands. Harvested areas with standing snags attract Red-headed Woodpeckers and Eastern Bluebirds as well as raptors, including nesting American Kestrels.

The traditional game species of white-tailed deer and eastern wild turkey have long inhabited and benefitted from active forest management and are sought after by the recreationists that utilize our southern forest lands. Deer thrive in areas that have been recently disturbed by forest management where lush herbaceous vegetation follows management such as final clearcut harvests or thinning. Turkeys utilize pine stands with open canopies for nesting and foraging, and hens take their broods to young stands that have lots of weeds and bugs to eat. Many a gobbler has been found strutting on open, grassy logging roads where traffic is restricted by gating, and the sun catches their iridescent feathers.

There is no better example of biodiversity conservation in working forests than the 40-year history of private forest landowners implementing voluntary BMPs for water quality protection. The South has a tremendous number of aquatic species including fishes, mussels, and turtles. These species have been conserved on actively managed forestlands yet have declined in non-forested watersheds and where dams have altered river flow. These aquatic species come by many interesting names such as the fat pocketbook mussel and candy darter, both of which are listed as endangered species, occupy stream reaches on our southern ownership, and are protected by our BMP implementation.

ENDANGERED SPECIES

As a custodian of its timberlands, PotlatchDeltic recognizes that some of its lands need to be conserved as forestland in perpetuity. We realize this goal through land partnerships, conservation land sales, and conservation easements. We work with a wide range of stakeholders for conservation, including states, cities, counties, water authorities, and environmental / conservation organizations including The Conservation Fund, The Nature Conservancy, and the Trust for Public Land. In addition, we commit to the protection of species at-risk and have entered into habitat conservation agreements to protect endangered species.

Through our conservation land sales, public agencies have increased forest ownership and connected parcels previously blocked from public access, while securing working forests for the future. Wildlife management areas have been expanded and availability for public recreation and hunting has been increased. Water management authorities have increased watershed protection and areas have been protected from future development. Cities and towns have increased land for infrastructure and public recreation and use.

PotlatchDeltic occasionally enters into formal agreements through conservation easements that limit timber harvesting or development on our timberland. We offer this commitment to conservation to support wildlife habitat and biodiversity or to preserve places and landscapes that have exceptional natural, social, or cultural value.

Across our timberlands and procurement basins, species ranging from the Canada lynx to the northern long-eared bat have been identified as endangered or threatened and are protected under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). For the endangered red-cockaded woodpecker that occurs on our lands in southern Arkansas, we participate in a Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP)16 with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to implement a variety of conservation measures for its unique habitat requirements.

Working forests are critical to the effort to conserve biodiversity. PotlatchDeltic combines scientific data with our decades of experience sustainably managing forest lands to advocate for policies and regulations that recognize conservation values and reward landowners for the contributions that our managed forests provide.

LEARN MORE ABOUT WILDLIFE CONSERVATION

Sustainable forestry requires a thoughtful balance between responsible resource management and the protection of ecologically, culturally, and historically significant sites. At PotlatchDeltic, foresters combine technology with hands-on expertise to identify and preserve these special places, so that forests remain productive while safeguarding their conservation value.

LEARN MORE ABOUT IDENTIFYING SPECIAL SITES

How does PotlatchDeltic conserve biodiversity across a land base that ranges from mountains to forests with dense, thorny vines and brambles? We do our homework! We work with partners, apply advanced mapping tools, conduct training, and make field inspections to locate and conserve rare species.

LEARN MORE ABOUT CONSERVING RARE SPECIES IN ARKANSAS

PotlatchDeltic occasionally enters into formal agreements with nonprofit and governmental agencies that limit timber harvesting or development on our forestland. We offer such easements to support the recovery of a threatened or endangered species, or to preserve places and landscapes that have exceptional natural, social, or cultural value.

LEARN MORE ABOUT THE RED-COCKADED WOODPECKER

On a warm spring morning, a native bumblebee hovers over a recently harvested section of a PotlatchDeltic forest, collecting pollen before darting towards a stand of young pine trees. This seemingly small act is part of a much larger story, one where sustainable forestry and pollinator conservation go hand in hand.

LEARN MORE ABOUT THE IMPORTANCE OF POLLINATORS

In Northern Idaho, elk, deer, and moose are vitally important to rural communities’ culture, traditions and economy and serve societal needs as game animals or subsistence foods. These large ungulates can also affect native vegetation and agricultural crops because of their large body size, diet choices, and widespread distributions. PotlatchDeltic recognizes the importance of these species and maintaining healthy herds in balance with native vegetation.

LEARN MORE ABOUT ELK / UNGULATES IN NORTHERN IDAHO

In Talbot County, GA a special site has been designated covering 99 acres to ensure the protection of the endangered Fringed Campion. The Fringed Campion is a low-growing, perennial herb that forms colonies by runners or stolons that creep along the ground. The species produces large, bright pink flowers with fringed margins that bloom in the spring. The showy flowers produce nectar utilized by beetles, moths, and butterflies.

LEARN MORE ABOUT THE FRINGED CAMPION

Native in the southeastern U.S., the Gopher Tortoise is a keystone species because it digs burrows that provide shelter for at least 360 other animal species. PotlatchDeltic gives special attention to Gopher Tortoises and protecting their habitat. Our foresters do so by tracking locations of known burrows and avoiding mechanical site preparation or harvests near them.

LEARN MORE ABOUT THE GOPHER TORTOISE

Listed as “endangered” by South Carolina, and as “rare” by Georgia, the Swallow-tailed Kite and its nesting area is a priority for protection by our foresters. We have a proactive plan in place that ensures protection of the majestic Swallow-tailed Kites that nest in our timberlands.

LEARN MORE ABOUT THE SWALLOW-TAILED KITE

Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) is a highly contagious fatal disease that affects deer and related species such as elk and moose. No cases of CWD infecting humans are known. The neurological illness typically causes infected animals to exhibit a shaggy coat, weight loss, and a wider wobbly stance. The disease was first detected in Colorado in 1967 but has since spread to 30 states and four Canadian provinces.

LEARN MORE ABOUT CHRONIC WASTING DISEASE